„I love the smell of book ink in

the morning” – Umberto Eco

One of the most enchanting places in Antwerp is the Plantin-Moretus

Museum.

An old publishing house, spacious and abounding in antique printing presses,

type specimens, proofs, design sketches and a superb library, its ornate

shelves filled with leather-bound books with exquisite frontispieces, the

Museum is a mecca for bibliophiles.

A UNESCO World Heritage site, to boot, it should not to be missed.

In 1548, a Frenchman, Christophe Plantin (1520-1589), moved with his wife to Antwerp.

In 1548, a Frenchman, Christophe Plantin (1520-1589), moved with his wife to Antwerp.

He set up a small business binding books and producing leather-covered jewel boxes.

Unfortunately, he fell victim to an assault

sustaining injury to his arm. He could not carry on his

trade as a binder, so to support his growing family he became a printer.

Little did he know this physical

injury would turn out a blessing.

Seven years after his arrival to this bustling

city of 100,000, at the crossroads of pan-European trade,

Plantin founded a

book publishing house.

Officina Plantiniana, ran by Plantin and later his two sons-in-law,

Jan Moretus (1543-1589) and Frans Raphelengius (1539-1597), continued as a

family business for nine generations until 1801.

When efforts to resuscitate it in the 19th century proved too

little and too late, the city of Antwerp bought the premises from the last

Moretus owner and turned this Renaissance gem into a museum.

The building complex at Vrijdagmarkt 22 evokes the glory days of an

incredible establishment.

Employing up to 80 workers – printers, typesetters, illustrators and

editors - with 22 presses, by the latter half of the 16th century the Officina Plantiniana became largest

publishing house in the world.

In his 34 years as a publisher Plantin would produce 2,450 titles in

Latin, Dutch, French, English, Greek, Spanish, Hebrew, German, Italian Syrian

and Armenian.

Some of the most successful books had print runs of 2,500 copies.

There were lots of breviaries,

catechisms, missals, psalters, biblical commentaries and horae, but not exclusively.

He also printed books on scientific

disciplines (beautiful herbaria; a world atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum by his friend, the brilliant Flemish cartographer

Abraham, etc.), philology, philosophy, literature, travel, even musical notes.

Plantin’s books were read across the Netherlands, the Holy Roman Empire,

France, Spain, Italy, England and overseas – in America, even in parts of North

Africa.

How Plantin managed to turn his dream into reality at a time of

religious strife, the Dutch revolt, the Spanish army’s push-back of ‘heretics’

and Protestant forces (much the same thing) remains a fascinating story.

Personal ambitions and business acumen helped, surely.

So did the patronage of the

supreme ruler of the Low Countries and one of the most powerful Christian

sovereigns of the time King Philip II of Spain.

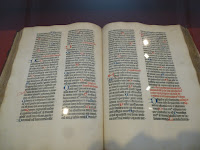

Plantin put forward to his royal patron an idea to produce the finest

Bible in all Christendom.

The king welcomed it and placed an order for a personal set.

After half a decade of Benedictine labour, requiring 40 workmen and a

slaughter of thousands of sheep, pushed on by the king’s personal librarian

looking over Plantin’s shoulder, he succeeded in a project that drove him to

the brink of bankruptcy.

The result was an exquisitely bound and decorated royal Polyglot Bible,

published on vellum in the original languages – Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Syriac

and Latin – and printed in eight volumes.

13 copies of this Bible were sent to the Royal Court at El Escorial in

1572.

11 of these Polyglot Bibles survive today - seven in Spain and the

others in London, Turin and the Vatican.

This feat won Plantin a privileged title of Arch-Printer to the King (Architypographus Regii).

Thereafter, he secured

many lucrative contracts, especially for eccleciastical works, that offset his

losses.

Last year, Christie’s put the only privately-owned Biblia Regia of royal provenance on sale.

The estimate was £600,000.

The final price went through the roof, setting a new record for a

Plantin work.

Plantiniana from my own collection

***

Judging by the standards of the Counter-Reformation Plantin was a

shadowy character.

While operating under license from King Philip II, a zealously religious

monarch, Plantin belonged to a sect known as the Familia Caritatis.

Inspired by the Dutch merchant Hendrik Niclaes, whom one scholar

described as “a visionary mystic who preached religious tolerance in an

intolerant age,” the members of the Family (inter

alia Ortelius) stood up for personal freedom in the face of all forms of

power.

They promoted tolerance as the foundation of the human brotherhood – one

Family, beyond national and religious divides, united by a deep inner Christian

faith.

As another scholar put it, the members of the “Family of Love” formed a

“small freemasonry of intellectuals dreaming of unity” that would bring about

an outpouring of art, science and commerce.

Against the backdrop of turbulent times, those “Christians without

Church” held on to a dream of an irenic utopia. (Would the ‘founding fathers’

of the European integration project not have been impressed?).

Mixing in these circles, caught in the act of printing ‘subversive’

tracts, pragmatic, cosmopolitan Plantin once or twice fled from the clutches of

the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition to a more laid-back France

until told by friends it was safe enough to return. He continued on and off to

conduct business with the Calvinists. Some of the books he published ended up

in the Index librorum prohibitorum.

Plantin’s ideals are reflected in the emblem printed on the title pages

of his books.

It shows a balanced compass with the motto Labore et Constantia: toil and steadfastness. A call for a diligent

pursuit of one’s calling in life, balanced by an advocacy of integrity and

constancy.

Perhaps in his approach to life Plantin (and his sons-in-laws) may have

been influenced by friendship with Justus Lipsius, a Flemish scholar, a towering

figure of the Renaissance, an author of works on neostoical philosophy (again, isn’t it interesting that the Council

of the European Union bears his name today?).

Plantin even had a room set aside for Lipsius at his publishing house.

It’s part of the museum circuit.

Like his father-in-law, the polyglot Jan Moretus, who inherited the

business from Plantin, was a perfectionist.

He popularised copperplate engravings.

He commissioned outstanding artists of the day to contribute to book

designs.

Peter Paul Rubens, for instance, provided illustrations for his new

prayer books. You can still see many of the original plates worked on by Rubens.

***

Visiting the Plantin-Moretus Museum is like time-travel.

In its 35 rooms, you can see the oldest

printing presses in the world (neat!), as well as hundreds of manuscripts,

dating to the 9th century, incunabulae, rare books (including 3

tomes fresh off the Gutenberg press), cartography, even some of Europe’s

earliest accounting ledgers (said to be an invention of the nineteenth-century). It even sports a Renaissance bookstore.

The Print cabinet has more than 20,000 drawings, including works by Anthony

Van Dyck, Jacob Jordaen and Rubens.

|

|

You can imagine as it would have been in its heyday – a beehive of

activity, thoughts being turned to paper, disseminated across the Christendom,

influencing hundreds and thousands of the literati, comforting the spiritually

needy or lighting intellectual fire to cast away the darkness.

A place of refuge for the wary soul.